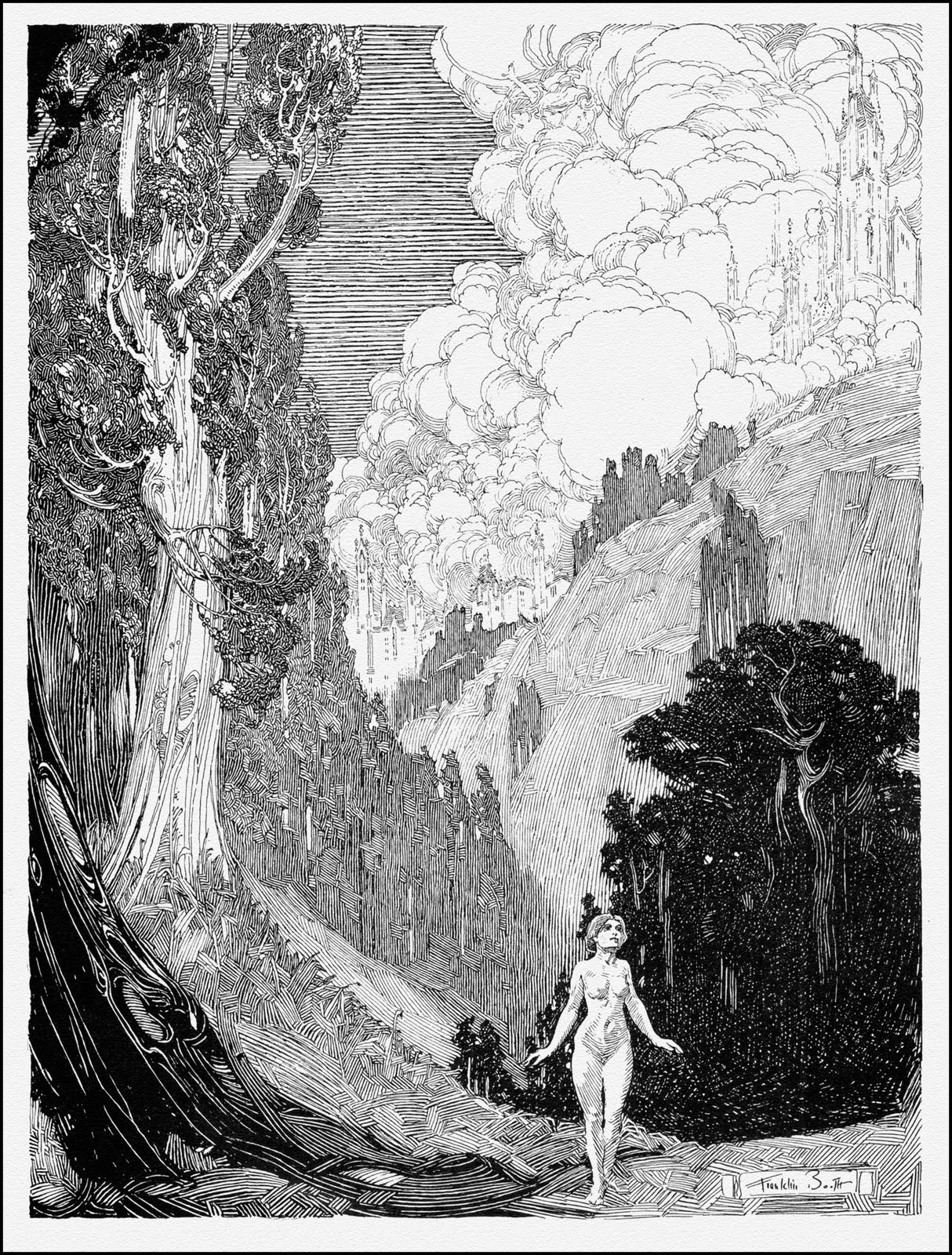

For most of my life I have been a fan of truly intricate artwork. Not necessarily photo-realistic, which I can take or leave, but art pieces that have wonderfully tiny details throughout. Think the engraving work of Gustave Doré, the incredible works of Franklin Booth, or the fascinating details created by Bernie Wrightson in his adaptation of Frankenstein.

However, something I often reflect on is the complexity behind a simpler piece, one that doesn’t have as many strokes. Sure, saying something is both simple and complex is kind of an oxymoron. After all, a piece is either complex or it isn’t, right? Whether we’re talking about the content or the artist’s technique, don’t I have to say that it is simple or complex, only one or the other?

Well, not really, since I am the one writing this I actually make the rules. Besides that, in Kuindji ‘s “After the Rain” we’re seeing both, even if it takes a moment to realize it.

If we start with the simple, the obvious, we can talk about the vision. It is a dark sky, but without much detail it does not come across as threatening. It is a simple landscape, with only a handful of soft trees and nearly featureless buildings. They are more the inference of humanity and nature, set in the broad landscape:

There is a dull light centered on the buildings, without much contrast. The light seems to be from a break in the clouds, with the gentle patterns just coming into play on the grassy plain. Only the road, and the livestock on the left, indicate that someone might actually live here.

Yet, all of these things betray the real complexity of the piece, both in content and technique. Kuindji could have chosen a bright sky, with as many details as the house. He could have painted people tending to the animal or near to the buildings, or even moved his vision closer to the home. In many ways, Kuindji painted a vision of humanity without humanity in it.

That is where the complexity of the content comes into play. Kuindji forces the viewer to decide how complex or simple the painting is to them. It’s easy enough to look at, see a farmhouse off in the field on a cloudy day, and move on. Or the viewer can immerse themselves in their own interpretations.

Is it a serene piece? The wide open fields and calm vision could be interpreted like that. The farm is getting sun after a rain, brightening up their world. You can almost smell the grass and the last of the rain, and as the clouds fade and the sun returns we are left with serenity. Think of Ave Maria or another calm classical tune softly playing in the air as you look at it.

For the more cynical of us (raises hand slowly…), this could be a tenebrous vision. The storm is coming, and it is merciless. Darkness creeps in from the viewer’s angle as well, and the lonely animal in the field might indicate that there’s no one left to care for it. Was Kuindji highlighting the farm because we’re about to see something sinister? Should we replace our Bach with Jóhannsson’s Sicario score? Kuindji used composition to keep us far away, at arm’s length. Keeping us out of the picture says that civilization is here, but humanity is not. At least, not any longer.

This is what makes a simple piece far more complex, and for me what art truly is. Kuindji laid all the expectations on the viewer, allowing them to decide what kind of image it really is. I think real art happens when it moves the viewer, when it brings them into the vision as a participant, and Kuindji did exactly that here.

In the end, being who I am, I think something sinister is going on. But I hold out hope that maybe we’re just in a serene valley, in a peaceful time, and all is well.

References

See previous editions and subscribe to new articles here.

See the larger version in the gallery

Arhip Ivanovich Kuindji

After the Rain

1879

105 х 161

Oil on canvas

Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, Russia

https://www.tretyakovgallery.ru/en/collection/posle-dozhdya-36311/