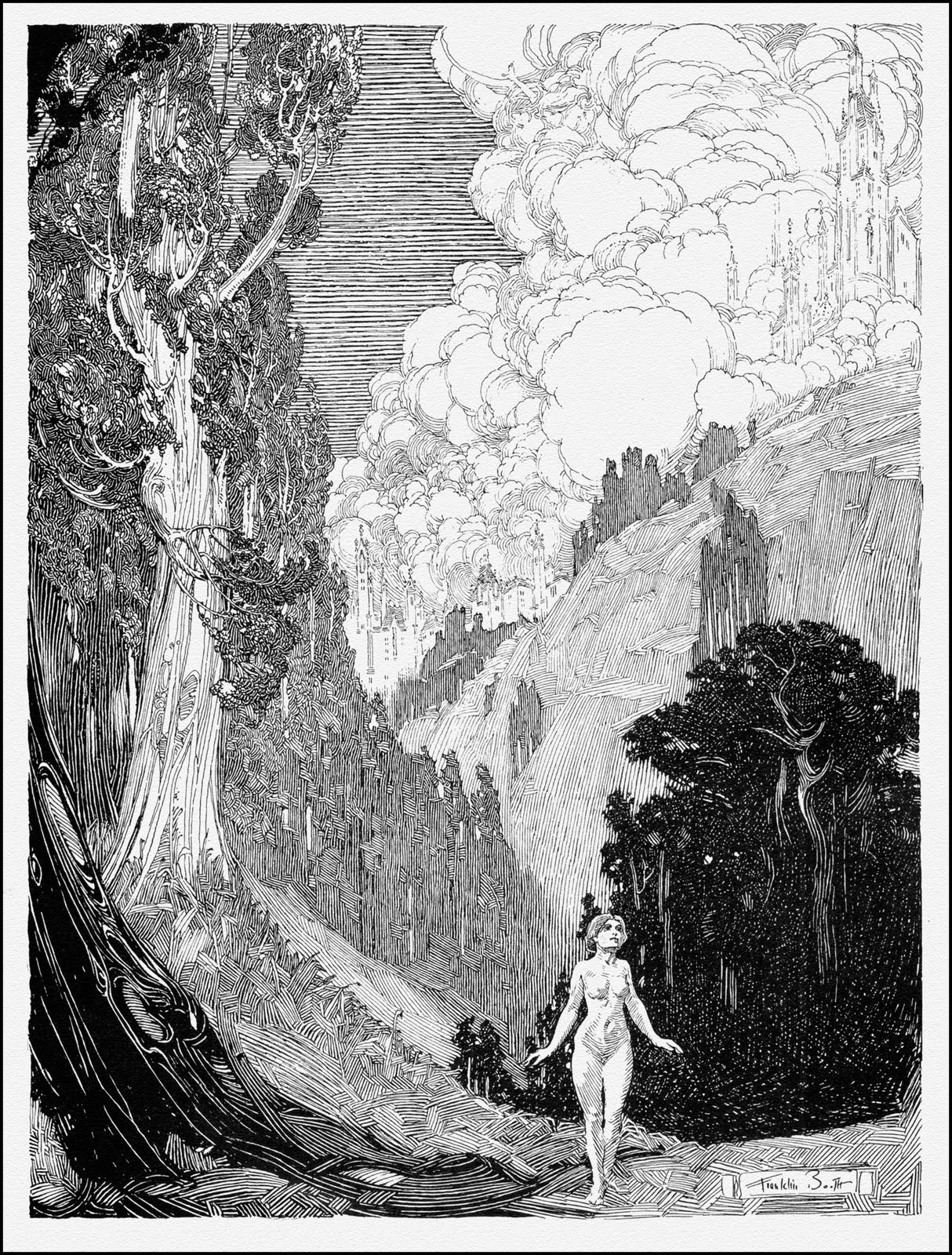

There’s a lot to unpack with Goya, especially for someone like me. I love traditional art, the kind you find in paintings that are hundreds of years old. I also love horror art, for those few fans I have left or those who have visited my art site it’s a fairly clear thing. So Goya speaks to me.

As much as I love his overall works, shown in great detail in the two Goya books that I am lucky enough to own, there’s just something about the so-called “black paintings” that I find intriguing. Goya painted the series during a rough patch in his life, and having been in similar positions often I know what it is like to use art as a catharsis.

Whether or not Goya was using the black paintings as catharsis or not is something I haven’t yet researched, and honestly might be something unknown. Artists are a fickle lot, sometimes we’re happy to talk about the process and other times a line is just a line, and leave us alone about where we want to put it.

I can certainly see Goya using these paintings to express something deep inside, something that maybe society wouldn’t agree with so readily. The painting is obviously dark, but in that darkness flies a flag of satire as well. Goya seems to have split his ideas right down the middle. Look at some of the details in a closeup:

Both horror and humor are evident in what Goya painted here. The old woman is expectant, even happy, yet the child she his handing over is a vision of horror. There’s the bright, almost smiling face of the devil himself, less a monster and more an indulgent party-goer. The woman on the right is seemingly beside herself, hurrying happily to hand over her child. Goya mixed the horror and cruelty of the ceremony with the joy and camaraderie of the witches around him.

One thing should delicately be pointed out about this painting is that Goya added sexuality to the mix of horror and satire. Goya courted controversy a number of times, particularly with clothed and naked versions of one painting that earned him some trouble from the Inquisition.

To go back to the delicate nature of the discussion, I don’t think there are any accidents in how Goya depicted sexuality here. The devil reaches over to his left, and he isn’t aiming for the child. The women around him are in various stages of undress, but not in the mythological or more alluringly soft methods of the late 18th century. This is cruder, more basic and almost feral, a sense that eroticism is just another part of the horror and, as it were, it’s own satirical statement on the culture of the time.

Goya was a very influential artist, and not just his ability to wield a brush and lob some paint at the wall. He could tell a complex story, and truly engage with his audience. It might be dark, sarcastic, even erotic in disturbing ways. But he left us an image that everyone could have some kind of opinion on.

See it larger on Google Arts & Culture

See previous editions and subscribe to new articles here.

References

El Aquelarre, or Witches Sabbath

Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes

1789; oil, canvas

44 cm x 31 cm

Museo Lázaro Galdiano, Madrid

http://www.museolazarogaldiano.es/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Witches%27_Sabbath_(Goya,_1798)