Parody has been a part of media and entertainment for centuries, with seemingly few public figures escaping notice. Parody and satire, particularly in politics and with public figures, dates back at least to a political cartoon by Benjamin Franklin from 1754, predating the United States as a country7. From political caricatures and books of the 19th century, through the Keystone Cops and comedy films of the 20th century, parody has been a vital part of American culture. Even in just the past few months, television shows such as Saturday Night Live featured acerbic parodies of public figures such as President Donald Trump.

While parody typically enjoys protection through the First Amendment as free speech, it is possible that parody can be offensive, even causing distress for public figures. The landmark Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) case Hustler Magazine, Inc. v. Falwell asked the question of First Amendment protection for offensive parodies, and effects on public figures. This paper summarizes the court case, analyzes the ruling based on the First Amendment, and evaluates the final ruling.

Summarizing the Case

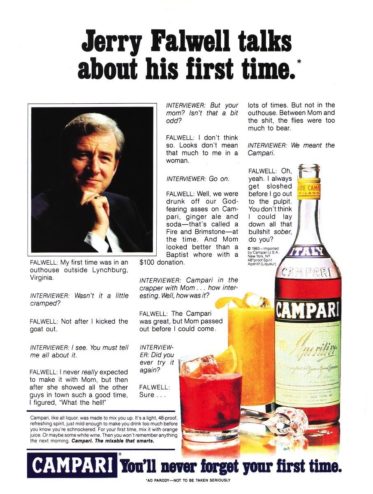

Hustler Magazine, Inc. v. Falwell centered on a parody advertisement (Figure 1), and whether or not the First Amendment protects offensive parody when it causes emotional distress to a public figure. In 1983, the sexually explicit magazine Hustler published a parody advertisement featuring popular Christian minister Jerry Falwell, satirizing the well-known Campari advertisements of the time5. The advertisement, carefully offering a parody disclaimer at the bottom, suggested that Falwell had lost his virginity to his own mother in an outhouse.

Despite the parody disclaimer, and listing in Hustler’s table of contents that the advertisement was fictional, Falwell sued the magazine. Falwell’s initial lawsuit was based on privacy invasion, libel based on the content of the advertisement, and “intentional infliction of emotional distress”5. Of those, the jury awarded Falwell damages only on the final charge of emotional distress, with Falwell awarded $150,000 in damages.

Hustler Magazine, Inc. appealed the ruling to the US Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit. Hustler Magazine, Inc. argued that the parody, no matter how outrageous, was protected under the First Amendment as free speech, but the Fourth Circuit found the level of outrageousness to be an irrelevant factor6. Hustler Magazine, Inc. also argued that a defamatory standard of actual malice against a public figure must be met, based on previous court cases6. However, the Fourth Circuit denied this approach as well, citing reckless behavior and protections against inflicting distress6. The Fourth Circuit upheld the decision in 1986 made by the lower court, and Hustler Magazine, Inc. appealed to SCOTUS for a final ruling.

SCOTUS ruled on the case in 1988, in favor of Hustler Magazine, Inc. and support of parody based on the First Amendment. The unanimous court ruled that the protections of the First Amendment trumped protection by the state for public figures against offensive parodies, provided that the parody could clearly not be taken as truth and that the offensive speech did not contain false statements of fact featuring “actual malice”8. The ruling only covered public figures, such as Falwell, and did not address parodies of private citizens.

Analyzing the Ruling

The SCOTUS ruling on the case gets to the heart of the First Amendment’s protections of free speech, and how that speech is communicated. The decision was a unanimous one by the court, and pointed out that outrageous speech could only be considered subjectively, as a jury would have wide-ranging tastes and personal views on the parody itself6. In a video interview given at the time of the decision1, Herb Block, Washington Post Cartoonist, supported the ruling and the methods that he himself uses in satire:

It doesn’t have to be the way you would do it, it doesn’t have to be in good taste, it doesn’t have to be something you agree with. It’s simply a matter of the person having the freedom to do it when it’s done in a satirical way1.

The court ruled on the emotional distress for public figures aspect of the case through the idea of reckless falsities. In describing the court’s ruling, As long as the satirist does not make false statements of fact, while recklessly ignoring the truth, the First Amendment takes precedence over liability2. SCOTUS ruled that parodies of public figures were a part of American culture, and that suing for emotional distress allowed public figures to drown legitimate and truthful free speech2. Public figures, including celebrities and politicians, have long been the targets of satire. Claims of emotional distress can chill not only free speech, but the freedom enjoyed by Americans to freely and openly discuss the public machinations of those figures, much of which affects the daily lives of citizens.

Figure 1: Hustler Magazine Print Ad. Retrieved from https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/qkbzjx/larry-flynt-profile-2016

As the daily lives of citizens could be affected by punishing creators of satirical works, even more so the court’s ruling found that the government should not take sides in American culture. The court found it unconstitutional to require standards of speech based solely on what a certain community finds appropriate3. American culture is a mixture of many different groups across the nation, and allowing one community’s guidelines of proper and improper speech is not what a government, which should remain neutral, can support3. Despite the explicit nature of Hustler Magazine and the potential for distress caused by it, the court decided that the clear parody was upheld by the First Amendment. What is offensive to one group may not be offensive to another, and limiting what can be openly said based on such limitations goes against the fabric of the freedom of speech laid out in the First Amendment.

Evaluating the Ruling

Much of the case relied on whether or not the outrageous nature of the parody was protected by the First Amendment, and in the shoes of a Supreme Court justice the decision could be a tough one. In the social media firestorms of the 21st century, allegations of fake news and the popularity of satirical media groups like The Onion and Cracked.com offer the American culture a possibly different modern view of the Hustler Magazine parody. The ease at which social media can turn a satirical article into a viral piece is something that did not exist in the 1980s, and services such as Snopes.com have evolved to counter untruthful claims.

The fierceness of how quickly false and satirical articles can spread unchecked through social media is a reminder of what Chief Justice William Rehnquist, overseeing the Hustler Magazine v. Falwell case, said about jury subjectiveness. In 2011, Justice Elena Kagan used Rehnquist’s words in a similar case, that outrageousness is completely subjective and would push a jury to award damages based on their own views4. The majority opinion by SCOTUS was that parody protections could lead to harsh, offensive, and even hurtful speech against public figures5. However, while obscenity does not get First Amendment protection, it is impossible to separate the outrageous from the culturally acceptable5. Allowing microcultures within society to decide what is acceptable, particularly in satire that often requires an amount of harshness against public entities, would chill the freedom of speech that the First Amendment is built on. The justices decided correctly that, much as Herb Block said, citizens do not have to agree with, condone, or appreciate satires and parodies. As long as there are no falsehoods, freedom of speech requires those statements to continue openly, without being restricted by cultural patterns.

Conclusion

Parody has been a part of media and entertainment in American culture for centuries, particularly in politics and with public figures. Parody typically enjoys protection through the First Amendment as free speech, but parody can be offensive, even causing distress to public figures. The Supreme Court of the United States case Hustler Magazine, Inc. v. Falwell asked the question of First Amendment protection for offensive parodies, and effects on public figures, and found that the offensive nature of parody cannot be chilled by the distress of public figures. This paper summarized the court case, analyzed the ruling based on the First Amendment, and evaluated the final ruling.

References

- ABC News. (n.d.). 2/24/88: Larry Flynt wins first amendment case. Retrieved from http://abcnews.go.com/Archives/video/feb-24-1988-hustler-falwell-12278659

- Chen, A. K., & Marceau, J. (2015). High value lies, ugly truths, and the first amendment. Vanderbilt Law Review, 68(6), 1435-1507.

- DeCosse, D. E. (2010). The Danish cartoons reconsidered: Catholic social teaching and the contemporary challenge of free speech. Theological Studies, 71(1), 101-132.

- From the bench. (2011). From the bench: U.S. supreme court. Newsletter on Intellectual Freedom, 60(2), 53-55.

- Justia. (n.d.). Hustler magazine, inc. v. Falwell 485 U.S. 46 (1988). Retrieved from https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/485/46/#annotation

- Justia Case. (n.d.). Hustler magazine, inc. v. Falwell 485 U.S. 46 (1988) full opinion. Retrieved from https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/485/46/case.html

- Katz, H. (2004). An historic look at political cartoons. Nieman Reports, 58(4), 44-46.

- Oyez. (n.d.). Hustler magazine, inc. v. Falwell. Retrieved from https://www.oyez.org/cases/1987/86-1278